[2025 Re-Post] Rigor Shouldn't Lead to Mortis

Is there more to rigorous instruction than pushing a bigger rock up a steeper hill?

(Image sourced here)

The Challenge

A perennial topic, so I thought I’d bring this one back and add a little to it.

Once upon a time, I attended a meeting of Chicago teachers, back when Arne Duncan was CEO of the public school system. He was introducing a new plan for a standardized but decentralized curriculum (schools could select programs from a menu of approved vendors), and he was talking up how this plan would increase academic rigor. Whereupon some teacher in the crowd stood up and yelled at Duncan that the CEO had no idea what “rigor” actually meant, and neither did anyone else in the room, and if anyone thought they did know, it was a good bet their definition wasn’t shared by anyone else in the district.

I don’t remember what Duncan’s response to the heckler was. It was probably ham-fisted and vague and ineffectual—which would not be surprising. Rigor is one of those words that people love to toss around without really knowing what it means. As Supreme Court Justice, Potter Stewart, famously said of obscenity, we know it when we see it. As pretty much everyone has said of beauty, it’s in the eye of the beholder. But should it be? Must it be?

A Healthy Workout

The easiest way to think about rigor is in terms of quantity: just give kids more to do. It’s a common way to address the needs of gifted and talented—or even just high-achieving—students. It’s also kind of a dumb way, because if students are doing a certain amount of X successfully, it’s not “rigorous” to make them do more of it. It’s not even particularly helpful. It’s just tedious.

If a trainer were going to put me on a rigorous workout regimen, would he simply add more reps at the weight he knows I can lift? Maybe, partly. Stamina does have its uses, in academics as well as in fitness. But if your goal is to get stronger, you have to lift more weight. The lift has to get harder over time. You lift what’s just doable, and you work on that for a while until it becomes easier. Then you add more.

There is a balance between dynamic quality (the climb) and static quality (the rest and recuperation) that Robert Pirsig talks about in his book, Lila. They’re both important. You can’t just climb and climb and climb. You have to rest, establish a camp, and get used to that new level as the new normal before moving on.

This idea of situating your workout in the place where it’s do-able but challenging should sound familiar, even to the least gym-ratty among us. In edu-speak, we call it the Zone of Proximal Development, or ZPD. It’s the sweet spot—the Goldilocks “Just Right” place—the most difficult level of work that a student can do comfortably. It’s where we would like every day’s classwork to be situated, for every single student.

That’s difficult to do when every student is in a different Just Right place. And it’s more difficult when, like the guy lifting weights in the gym, the Just Right changes over time. To maintain rigor, you have to know exactly where a student is at all times, and situate the work right at the leading edge of that ZPD. It’s a serious challenge. It’s why a one-size-fits-all curriculum fails, and it’s also why tracking students into different rooms for an entire semester fails. A single benchmark assessment only tells you where a student is on test-day. But that student is a forever-moving target.

What Matters Most

What does it mean to know “where a student is?” In math (and sometimes science), you can assess knowledge or mastery of discrete topics and skills. You master one and then you move on to the next thing or the next level. In the humanities, though, which is less modular and discrete, it can be trickier. Once you can read at a high Lexile level, you’re a skilled reader. Once you can write at a collegiate level (or close to it), you’re a skilled writer. What constitutes “harder?”

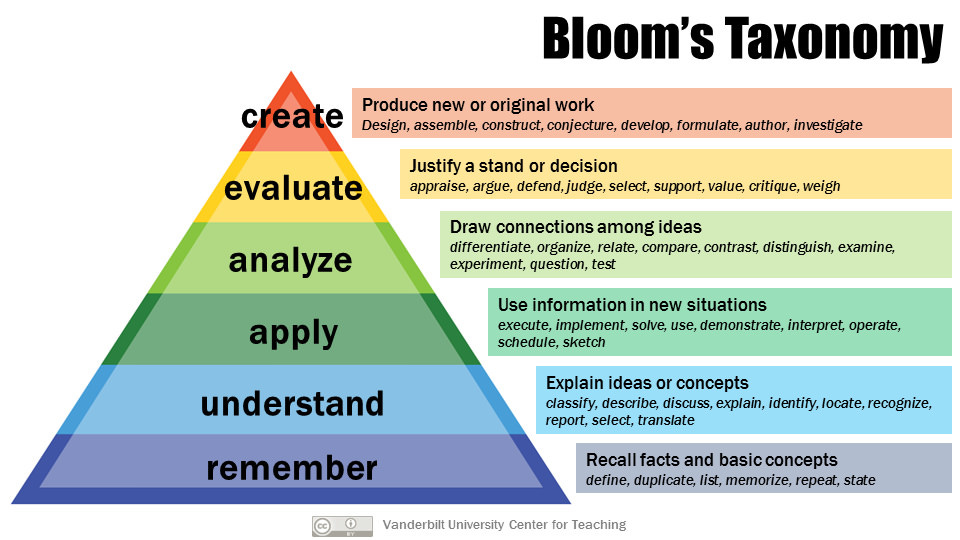

When we want to increase rigor and push students to go further—in any subject—we can increase the cognitive complexity rather than just moving them on to the next topic. Benjamin Bloom’s taxonomy provides a handy guideline for teachers, showing factual comprehension as a base level, and working up through analysis to evaluation and, ultimately, creation of new content. This can help teachers take the same set of content and change what kind of work is expected of each student.

Of course, that can be a challenge for teachers, as it gets harder and harder to evaluate student work, the higher up the pyramid you go. Comprehension of basic facts and performance of basic skills are relatively easy to assess, but how do you know whether a student’s analysis, evaluation, or original creation is fair, good, or great? Once you get up to the tippy-top, a simple answer key won’t do the trick.

Norman Webb’s Depth of Knowledge (or DOK) is another system for defining rigor. Webb posits four levels of depth, with Level 1 focusing on basic recall and comprehension tasks, and Level 4 focusing on in-depth, time-intensive tasks. Webb’s addition of time—extended thinking and work—is interesting and useful: a week-long research project is likely going to be more rigorous than a homework assignment.

But, again, the evaluation burden on the teacher increases as the rigor demands on the students increase. Rigor makes demands on everyone.

One of my favorite takes on rigor doesn’t involve levels at all. Richard Strong, Harvey Silver, and Matthew Perini, in Teaching What Matters Most (ASCD, 2001) describe rigor as, “the capacity to understand content that is complex, ambiguous, provocative, and personally or emotionally challenging” (p. 7). I think that’s an interesting construction. The authors aren’t satisfied with mere complexity. They want students to be able to handle ambiguity and provocation—not merely theoretical provocation, but material that challenges the student personally. Each element of their formula adds rigor to an assignment by itself; when those things work in combination, they can increase challenge (and, likely, engagement) significantly. And tasks or problems that are complex, ambiguous, and provocative are much more like what we have to grapple with in our adult lives.

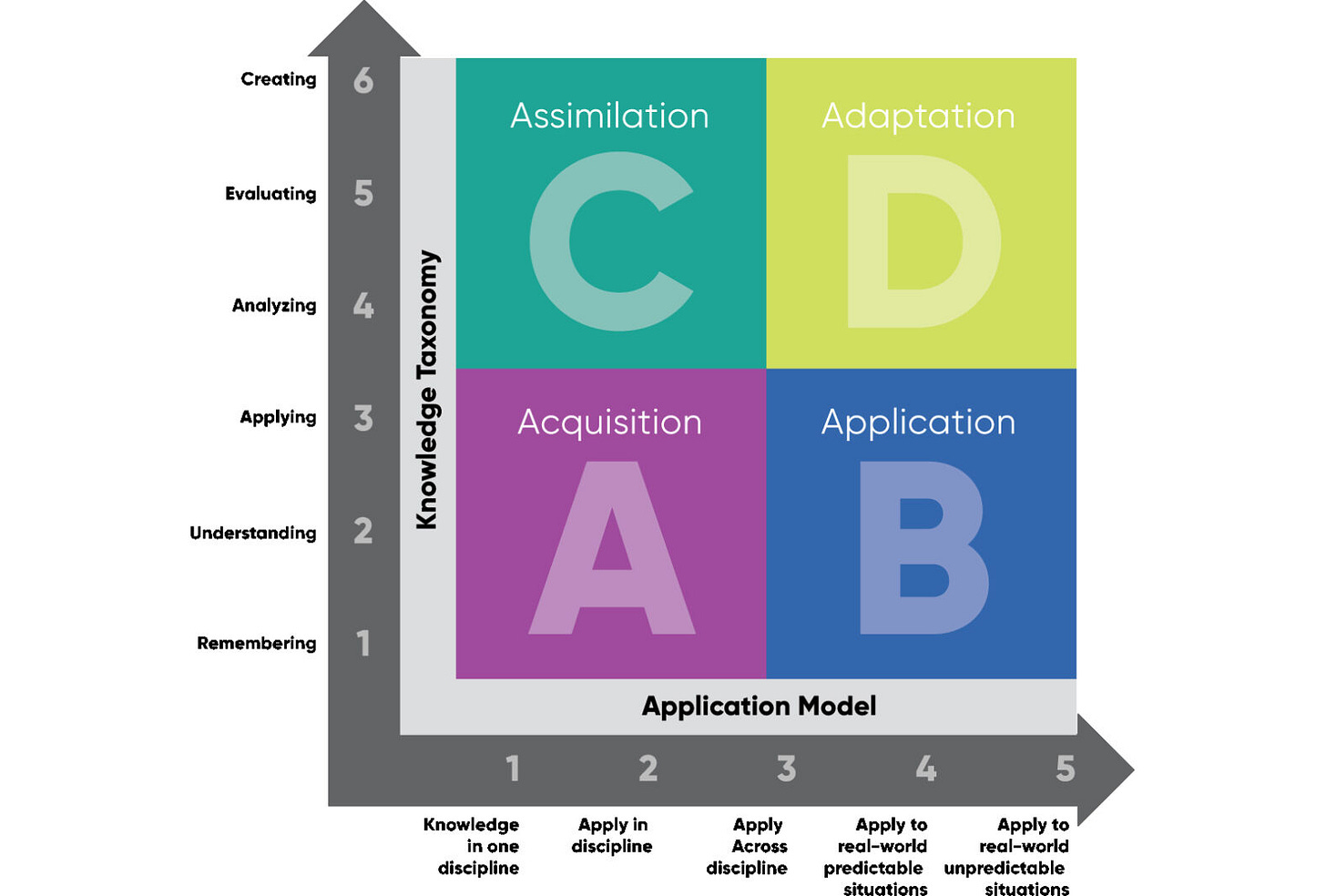

This simulation or approximation of real-world-ness is an important element of the Rigor-Relevance Framework, developed by Bill Daggett. The framework creates a quadrant map, with Bloom’s Taxonomy forming the vertical axis, showing increasing cognitive complexity, set against a horizontal axis that speaks to application—starting with knowledge and use within one classroom discipline, then moving to application across disciplines, then going outside the classroom into real-world but clear and predictable situations, and landing, finally, at real-world application in a messy, unpredictable situation. For Daggett, real rigor is the ability to work at the highest cognitive levels (evaluation and creation), in the messiest and most ambiguous contexts. If you can do that with your content knowledge, you can really make use of your education out in the adult world.

Getting Stronger Every Day

What is the result of a rigorous physical workout regimen, sustained over time? You build muscle. Your body changes. It is no longer what it was. If we worked with a trainer for a year and saw no physical change in ourselves, we would be dissatisfied.

What is the result of a rigorous education, sustained over time? You build mind. Your thoughts change, and the way you think changes. You are no longer what you were. If the child moves from one grade to the next and has not grown and changed in what she knows and how she thinks, even a little, parents should not be satisfied. You should not escape from your education untouched.

And yet, it’s exactly that kind of growth and change that has been the focus of parents’ ire and activism in recent years. God forbid the school should provide opportunities for students to challenge their own preconceptions, to broaden their understanding of how the world works. Somehow, we’ve been led (or forced) to believe that what a child thinks and how a child thinks are…none of our business as teachers.

I guess the idea is that the content of a child’s mind is the sole responsibility of the home and the church, and that the school’s job is merely to reinforce and strengthen whatever ideas and opinions the child comes in with. Apparently, we are supposed to provide a variety of safely vetted facts, and hone a variety of state-mandated skills, but we must ensure that the child never actually changes her mind or her opinion about any of those facts or applies those skills to develop her own ideas.

This is dangerous nonsense—and no less dangerous for it being nonsense. A nation that is afraid of looking at things from a different angle, considering things from a different perspective, is a nation that is calcifying. A community that is afraid of its children learning facts that their parents might not have learned or developing opinions different from those of the adults is a community that is frightened by a changing world (which, I’m sorry to have to tell them, is the only world we have).

We are better than that. Or, rather, we should be better than that. If we want our children to inherit a strong and dynamic country, we must be better than that. We must be as strong and dynamic as the challenges we have to face.

So, I don’t know—maybe there isn’t more to rigorous instruction than pushing a bigger rock up a steeper hill…as long as you realize that neither the rock nor the incline are stable or predictable. The rocks get bigger, but they also change shape. Sometimes they turn into Jello and fall apart when you apply force. Sometimes they feel like they’re inside you, not in front of you. And the hills get steeper, but also windier, and dense with undergrowth, with the pathway hidden from view. Sometimes you have to make the path, yourself—you and your rock.

But that’s life, right? Rolling a little ball around on a level floor is baby stuff.

It doesn’t stop when you graduate from high school. It never stops. The world is complex; understanding it takes a lifetime. It’s our life’s work, so we might as well embrace it—and even enjoy it. As Camus said, “one must imagine Sisyphus happy.”

In a world of disinformation I think we know less now than we did twenty years ago. As you imply, if the teacher has her student take on the daunting task of separating fact from political fiction, she may be looking for a job.