A Standard Take on Writing

The rest of the world uses the word differently than we Ed Folk do.

Free-for-All

Sometime last year, I read a post from a high school teacher who was fed up with assigning and grading five-paragraph essays. He found them banal and drab and uninteresting, and he found it difficult to give students meaningful feedback. The whole task was drudgery, he felt—for him and for his kids.

I felt his pain. Bad writing assignments are a plague. Students hate them; teachers hate them.

This teacher’s solution? He said that as far as he was concerned now, the kids could write anything they wanted, any way they wanted, because self-expression and self-actualization were more important than conforming to some ancient and arbitrary structure of writing that no one really cared about. Enough! The new writing syllabus became, “you do you.”

How that was meant to be different from what his kids did on their phones all day outside of school? He didn’t say. Maybe he didn’t care. Maybe he felt that, at the exalted age of whatever they were—15?—they were as adept at written communication as they needed to be.

Also, he had nothing to say about how he intended to grade those assignments or give feedback on them. Maybe he wasn’t going to. Or maybe he was going to reserve the right to be just as subjective and random as they were. You do you; I do me. I don’t know.

As you can tell, I found the whole thing depressing. I didn’t respond to it. I just pushed it to the back of my mind and let it sit there for a while, because it was the holiday season, and I had a kid getting ready to go back to college, and there was probably laundry to do, and…you know. I was busy.

But I know why I found it depressing. It felt irresponsible. I know teachers are still grappling with post-COVID learning loss. I know they’ve been forced to carry more of the burden of character building and moral instruction and self-esteem building and a hundred other things. But none of that changes the fact that one of the critical jobs of an English teacher is to make sure that a student can put thoughts to paper—thoughts, not just emotions—and can do so effectively for a variety of audiences.

Let’s not get into the whole issue of kids using AI to do their writing. I’ve opined on that before, and it’s a whole different conundrum. Let’s stay focused on the topic of actual human students doing actual human writing to express what they actually have learned (which I have also written about before).

I have no objection to, “write whatever you want” (not true—I have some objections), but I have real objections to, “write it however you like.” I’ve seen a lot of that in schools, and, as I said, it feels irresponsible. It surrenders the need for instruction. There’s no “right” way to do anything, so don’t worry about it. Whatever you come into the classroom with is what you’ll leave with. That feels like we’re cheating our children. And it puts all the burden of comprehension onto the reader. It says, “I’m expressing myself my way. If you care, you can do the work required to understand it.”

In other words, it’s a free-for-all for students, which is not free for the rest of us. Readers pay the cost. And that’s not right.

No one owes us their attention, and they certainly don’t owe us exertion just to understand us. If you want to be heard, you need to speak clearly. You need to do the work. And the “work” has to be something that works for anyone or everyone—communicating in a way that a variety of audiences will be able to understand—expected audiences and unexpected ones—known readers and unknown readers. Anyone. The whole benefit of written communication is that can reach people beyond your circle of friends—beyond shouting range. Which is why teaching some standard formats and genres and rules of writing matters.

It’s why standards matter, all around.

What is the Standard?

In ed-world, we’ve come to think of standards as mandates or requirements or goals or objectives: dreary and burdensome things that creative and freedom-loving people dread and resist. But in the rest of the world, a standard is simply an agreed-upon unit or process that allows large groups of people to work together smoothly. It is meant to lift burdens, not add to them.

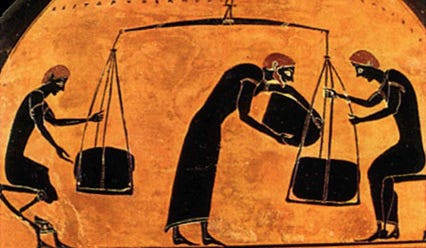

We use standardized weights and measures. They allow us to understand what we’re buying at the grocery store, how to make a recipe, how to construct a chicken coop—all kinds of things. Cultures have sought to standardize things like weights and measures for ages; the earliest examples stretch back to the third and fourth millennium, BCE. I don’t hear people bitching about the tyranny of the inch.

When objects and processes we use in everyday life are not standardized, things like building and crafting can be wildly idiosyncratic, or deeply mysterious, passed down individually from master to apprentice. The only right way to do a thing is the way your Master did it.

There’s nothing wrong with that old method—it captured and communicated time-tested methods and processes in many times and places. But it kept knowledge secret and special. Only certain people knew how to do certain things (and those people often formed guilds to protect their monopolies). Standardization is the process of collecting, sharing, and formalizing the things that work, so that everyone can make use of them.

We like standardization. When we have to deal with things that aren’t standardized—like USB plugs in the early days, like VHS vs. Betamax in the early days—it irritates us to no end, because, just as with the writing example above, it forces us to do the hard work of making things make sense. We have to figure out which thing to use, or which process to use, or how some wacky genius decided to put the puzzle pieces together this time, for this product. It’s not bad, per se; it just makes more work for us. It’s annoying. That’s why we (eventually) standardized spelling—so we wouldn’t have to stare at a word and say, “what the hell is that supposed to mean?”

The essay—even the dreaded five-paragraph essay—is a just a standard format for communicating ideas and arguments in writing. It’s a vehicle for carrying information in a logical and structured way. It comes from the French word meaning, “to try.” It’s a structure for trying out your ideas—taking them out for walk along a logical, linear pathway that other people can follow.

Most people are familiar with the essay and know how to navigate it—if not as writers, then at least as readers. We know where we’re liable to encounter the central argument or point of the essay. We know how that thesis is going to get broken down and argued or explained. We expect it to be get broken down. We expect it to be argued or explained. Here’s what they think; here’s why they think it; here’s why it matters. It’s a highly efficient vehicle for delivering arguments and ideas into our brains.

It’s not an exciting structure; structures are rarely exciting in themselves. You can season a pita chip all you like, but its main purpose is still to scoop up something tastier and deliver it into your mouth.

The essay is the pita chip of rhetoric.

If we find the structure boring, it’s probably because we’re using it in boring ways and refusing to scoop up interesting ideas with it. The topics we force students to address may be putting them, and us, to sleep. If teachers are getting boring essays, it may be because they’re assigning boring topics.

It may also be because teachers are using the entire essay as their unit of instruction, which makes focused feedback hard to give. They feel like they have mark-up entire papers, all the time, and it’s exhausting. It’s exhausting and frustrating for kids, too. What are they supposed to do with all of those red marks on papers or track changes on screens?

If these teachers (or their predecessors in earlier grades) have skipped over the writing of sentences and the crafting of paragraphs, there’s only so much they can say about the essay as a whole. We need to spend much more time, even after elementary school, talking about what makes for a powerful sentence, a beautiful sentence, a compelling sentence—experimenting with how word choice and syntax and rhythm can affect meaning.

Likewise with paragraphs. When I was teaching, it drove me crazy to get two-sentence paragraphs from kids—a topic sentence plus a sentence of support. The end. It was my own fault, though, because I hadn’t really taught them what a paragraph could do—what it really meant to elaborate on and explain an idea, or how one could explore supporting evidence. I didn’t know enough, myself.

At least I never told them that the only important thing about a paragraph was that it had to contain five sentences.

Another problem may be that we’re using the essay as the only form of communicating ideas in writing. Imagine if teachers had students address the same topic using different writing methods, one after another: an descriptive essay about the autumn, followed by a short story, followed by a poem or a song lyric, to help students understand the unique powers and limitations of each form of writing, and how each can unlock and bring forth different ideas and feelings on the same topic.

Language is a flower and a prayer and a weapon, and all day long, we reduce it to a mere task.

Short-Circuiting Thought

HOWEVER.

The convenience of learning how to use a standard structure or process can sometimes short-circuit thinking. It can encourage students to work by rote. We teach standard algorithms for problems-solving in mathematics to help students get to a solution faster: a particular way to do long division; a particular way to multiply multi-digit numbers, and so on. It’s not unusual for students to become proficient at executing those processes without really understanding, conceptually, why they work or what, mathematically, is really happening (I speak from long, personal experience). This leads to a kind of limited fluency that can hit a wall as soon as the math becomes complicated. You’re doing, but you don’t really understand what you’re doing.

Are essays similar? Do students paint by numbers without really thinking about what they’re doing? You know they do. There’s a reason the teacher I mentioned at the top got bored with the essays his kids were writing. Getting kids to do is hard enough; getting them to think about what they’re doing can be seriously challenging. But that kind of self-reflection and metacognition is where real learning happens. And a lot of that happens in the act of writing.

Students think writing is a chore that they’re forced to do only after they’ve learned a thing and know all about it, but that’s not true. Often, we figure out what we think by writing about it. We don’t really know until we tell ourselves. The first audience we have to communicate with is ourselves.

How much have we downgraded this important art and craft? There are kids in college today who are having AI read for them, summarize for them, and write entire papers for them. For all I know, there are professors using AI to grade those papers. The humans may be left entirely out of the equation.

(New Yorker Magazine, June 30, 2025)

Doesn’t it make you wonder: what’s the point of being in that class? What’s the point of being in college at all?

Children don’t enter our school systems bored, bland, and incurious about the world. If they end up that way, it’s our fault—at least in part.

Their innate, hard-wired curiosity is our raw material; what we do with it is up to us.

The most sane, logical debate on education, specifically writing, I’ve read in a long time. In Texas the mandated standardized testing has become the entire curriculum . Teach the test…. And so anything else that hints at standardized is seen as a misery. Your piece really speaks to both sides of setting standards👍